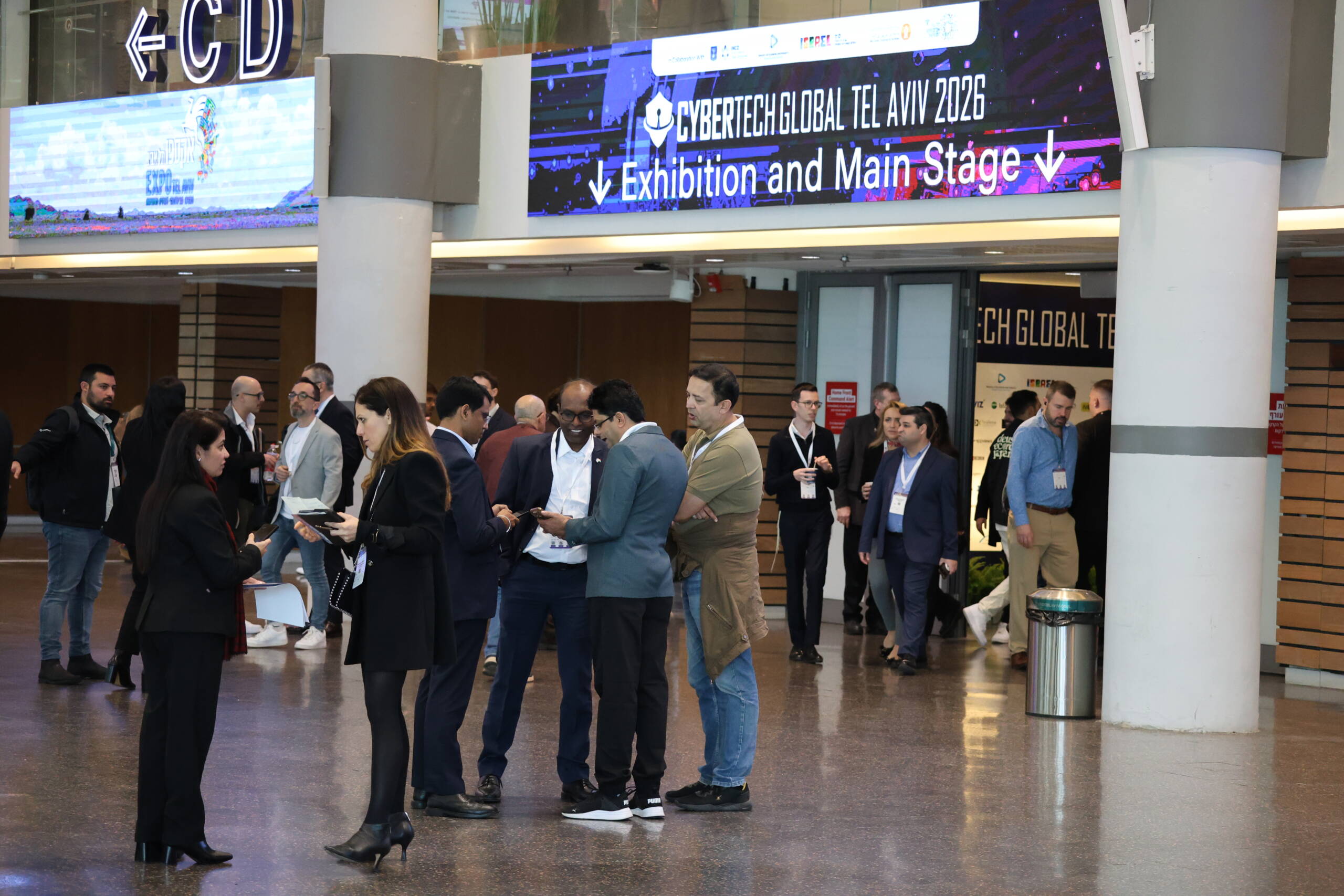

Cybertech 2026 unfolded at Tel Aviv Expo like a living organism rather than a conference, three days of constant motion where conversations overlapped, ideas collided, and the air itself seemed charged with urgency. Pavilion 2 was never quiet, not even for a moment. You’d step off one discussion about AI-driven attacks and land straight into another about quantum resilience or supply chain exposure, as if the event itself was designed to simulate the environment everyone was talking about: overloaded, interconnected, and impossible to pause. Walking the floor, it became obvious that cybersecurity is no longer treated as a vertical. It has dissolved into everything else, into energy, transport, finance, government, and even diplomacy, and Cybertech 2026 made no attempt to separate those threads. The agenda alone read like a map of global anxiety, stretching across AI, national resilience, critical infrastructure, misinformation, and the slow collapse of digital trust, all packed into a schedule that felt almost intentionally overwhelming.

On the main stage, the tone shifted from motion to gravity. Yossi Karadi, Director General of the Israel National Cyber Directorate, stood behind the podium under harsh white lights, his image multiplied across the massive screen behind him. The backdrop repeated “Cybertech Global Tel Aviv 2026” like a mantra, but his presence grounded it. He spoke with the calm precision of someone used to systems under stress, hands moving minimally, eyes steady, the kind of posture that signals responsibility more than performance. This wasn’t a keynote about innovation for its own sake; it felt like a status report on a system that never sleeps. The audience listened differently here—less applause, more stillness—because this was about infrastructure, not optimism, about what breaks first and what must never break at all.

Yossi Karadi, Director General, Israel National Cyber Directorate

Then, back on stage, a moment that silenced the room in a completely different way. Noa Argamani, BGU Computer Science student and captivity survivor, sat under the same lights, holding the microphone with both hands, her voice steady but carrying weight that no slide deck ever could. The background screen still repeated the Cybertech branding, but suddenly it felt distant, almost irrelevant. She spoke not as a symbol, but as a person who had crossed from abstraction into reality and back again. In that moment, cybersecurity stopped being about systems, AI models, or attack surfaces. It became about people, about continuity, about the fragile thread between digital infrastructure and human life. You could see it on faces in the crowd—this was the talk everyone would remember, even if they couldn’t yet explain why.

Noa Argamani, BGU Computer Science student and captivity survivor

The main stage set the tone early. AI was no longer introduced as innovation; it was described as force, something closer to weather than to software. Executives from NVIDIA, Wiz, Check Point, Nebius, and others spoke about AI the way engineers talk about electricity grids: powerful, necessary, and unforgiving when badly designed. The idea that AI now sits on both sides of the battlefield ran through almost every session, and the audience felt it. These weren’t visionary talks filled with buzzwords, but operational conversations about real systems already under strain. SOCs, cloud environments, identity layers, and data pipelines were described as living systems being pushed beyond their original design limits, and nobody pretended otherwise. You could sense the shift in the room when speakers talked about coexistence rather than control, about managing risk instead of eliminating it. That language alone said a lot.

What truly distinguished Cybertech 2026, though, was how seamlessly state power and startup culture merged. Ministers, former intelligence chiefs, national cyber directors, and regulators didn’t appear as formalities; they were part of the working conversation. Panels on maritime security, aviation, railways, smart cities, and supply chains felt less like theory and more like emergency planning sessions held in public. When port authorities and transport officials spoke, they spoke with the calm of people who already know systems will fail and are focused only on how fast they can recover. On the exhibition floor, this translated into startups pitching not just products, but operating philosophies: how to survive, how to reroute, how to keep functioning when everything is under attack at once.

The real Cybertech, as always, happened between sessions. In corridors and coffee lines, investors recalibrated quietly, founders compared notes with tired honesty, and CISOs exchanged stories that never make it into keynotes. There was fatigue in the air, unmistakable and human, but also a kind of brutal clarity. October still hung heavily over many conversations, shaping how Israelis spoke about resilience, continuity, and the cost of complacency. When speakers talked about restarting life, designing security from day one, or rebuilding trust, it didn’t sound like metaphor. It sounded lived-in, almost raw, and it gave the entire event a gravity that’s rare in tech gatherings.

Bezalel Eithan Raviv, the Founder and CEO of Lionsgate Network, an Israeli blockchain forensics company ranked third in the United States in cryptocurrency fraud investigations.

By the final day, when discussions turned toward disinformation, fake content, financial manipulation, and the erosion of truth itself, Cybertech stopped feeling like a cybersecurity conference altogether. It began to feel like a rehearsal for the next decade of governance. The questions were no longer only about protecting systems, but about protecting reality—what can be verified, what can be trusted, and who decides when machines can convincingly lie. Walking out into the cool Tel Aviv light, past banners and half-packed booths, it was hard to avoid the conclusion that Cybertech 2026 marked something subtle but important. Not a solution, not a breakthrough, but a shared acknowledgment that cyber is no longer a problem to fix. It’s an environment we inhabit now, and everyone here was trying, in their own imperfect way, to learn how to live inside it.

Leave a Reply